Author’s Note: The words “women” and “female” are used in this blog to refer to biologically female-sex-at-birth individuals. This wording does not assume gender identity and is not meant to exclude anyone who has experienced any issues discussed.

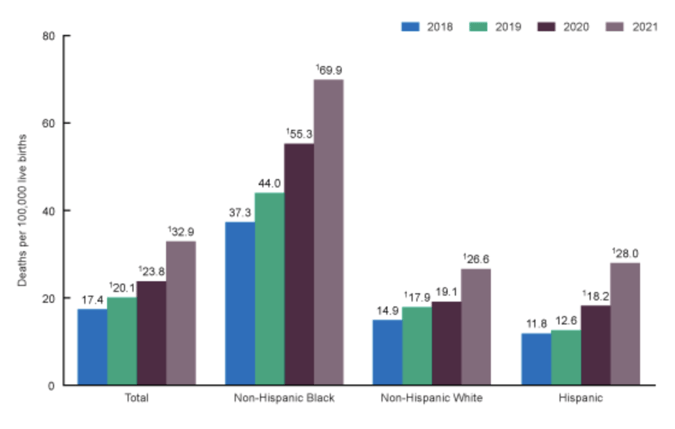

The US is facing a maternal mortality crisis, as declared by the Biden-Harris Administration and demonstrated by the numbers: 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births on average in 2018, compared to 8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births in the next worst performing wealthy nation as shown in The Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 report. The rate for non-Hispanic Black women was more than double the average at 39.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in the same year.

In February of 2023, the CDC released updated statistics for 2021; the national mean has almost doubled since 2018 and is now at 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births. For non-Hispanic Black women, the number is 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, the same as Peru’s estimated national average from 2020, a country whose GDP is 2% that of the US.

In February of 2023, the CDC released updated statistics for 2021; the national mean has almost doubled since 2018 and is now at 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births. For non-Hispanic Black women, the number is 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, the same as Peru’s estimated national average from 2020, a country whose GDP is 2% that of the US.

While the racial disparities are unfortunately not surprising, an important trend to note is that this rate is increasing for everyone, not just low-income or minority populations who often experience worse-than-average health outcomes. Even for the youngest group under 25, who typically have the healthiest, least complicated pregnancies, the mortality rate has gone from 10.6 in 2018 to 20.4 per 100,000 in 2021 overall.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.htm

COVID-19 likely played a role in this dramatic increase, but similar to how the pandemic exposed so many shortcomings of our healthcare system, the dismal results we saw prior to 2020 prove that system was already failing to meet a basic need of women. An important clarification to highlight this point is that according to the CDC, 4 out of 5 of these deaths were preventable.

Maternal mortality is an easy statistic to start with because the numbers are so shocking, but these types of results are not unique to the birthing process. Women have been experiencing fragmented, incomplete, and often negligent care throughout their lifetime for as long as we have had an organized healthcare system in the US (and really much longer). Pregnancy and birth are periods of high surveillance and medical interaction for women, and therefore have substantial data surrounding them, however, female health is a continuum of care that begins much earlier than, and extends far beyond, giving birth.

Despite the very predictable health requirements of women throughout their lives, these needs are often not supported in traditional primary care settings. We see this in the improving, but still disappointing, rate of HPV vaccination in 13-17 year old females at 52.2% and the extremely low percentage of primary care providers who offer the full range of contraceptive options. We know that unplanned pregnancies result in worse birth outcomes for mothers and babies and fundamentally alter a woman’s life, yet 45% of pregnancies in the US were unplanned in 2011 (interestingly, 2011 is the last time national rates of unplanned pregnancies were published). And while I have focused much of this blog on birth outcomes, those numbers tell only part of the story.

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), for example, is one of the most common reproductive disorders in women yet remains chronically undiagnosed and untreated. Menopause impacts every female in the world, and despite women reporting significant challenges to their work and lives, most providers and women themselves are not educated on how to discuss and manage symptoms. In analyzing these patterns across the US healthcare system, the evidence suggests that we have failed to prioritize women’s health, to the detriment of individuals, communities, and the entire population.

The statistics around these specific points of care prompt questions about the role systemic forces play in fueling these unacceptable results. This does not just matter for individuals – there are profound impacts on families, communities, and the healthcare system when women’s health is ignored. In the US’s quest to move to value-based care, we seem to have forgotten half the population, and it will never be possible to improve individual and population health at lower costs without a greater emphasis on women’s health outcomes. We must decide, collectively, that women’s health matters, and draw on past examples of public health successes to chart a path forward.

Many population health achievements in the US have resulted from coordinated approaches that combine large-scale research, behavioral change efforts, and health practice transformation. Lowering smoking rates is an excellent example of this process; after enough studies were published showing the connection between people who smoke and those who develop lung cancer, healthcare providers became united in both counseling against smoking and providing assistance to quit.

CMS requires community health centers to report rates of tobacco screening and cessation, every doctor asks about smoking status, and there is a myriad of national quit lines, support groups, and medications to help individuals stop smoking. From the policy perspective, most states have indoor smoking bans in public spaces, and no one is allowed to smoke on an airplane anymore. Smoking rates have been cut almost in half in the last 16 years, from 20.9% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2021, a resounding public health success by any measure, especially considering how difficult it is in the US to institute long-term health behavior changes (though of course the rise of vaping poses a new challenge).

While reducing smoking rates is a far more specific public health challenge than “improving women’s health,” there are elements of the former model that can be applied here. First, we must all agree that women deserve and require quality care. Given the numbers cited earlier and what we know about a lack of female-specific healthcare research and data, it is clear the United States, collectively, has not adequately prioritized women and their health.

Women make up half the population, contribute to the economy and households, and carry and give birth to all babies. When their health is ignored and, in many cases, made worse by policy and socioeconomic choices and forces, the entire country suffers. Women contracting cervical cancer from preventable HPV infections, facing infertility risks from undiagnosed PCOS, navigating unplanned pregnancies, dying from childbirth, and struggling to work because of ignored menopause symptoms (to name just a few) has economic and social consequences for everyone, not just females.

We must change the way we conduct healthcare research, both in terms of including more women in clinical trials and diversifying the women represented. We must build tools into our systems of care to remind and encourage providers and teams to ask the right questions and consider the larger context. These checks are already happening for some conditions; breast cancer screening, for example, is part of routine care for women and it is standard practice for primary care providers to suggest mammograms to female patients. Most women, thanks to aggressive public health campaigns, are also aware that there are screening options for breast cancer. But this is a small sliver of what makes up “women’s health” and we need to do better.

At Azara, our goal is to surface relevant information to support population health, value-based care, and the quintuple aim. The same tools that do this can also be used to make prioritizing women’s health the norm. The Patient Visit Planning (PVP) report, for example, helps prep care teams for the day and reminds them of what gaps can be closed during the visit. This tool goes beyond helping to improve measure performance – it assists in delivering impactful, life-altering care.

Practices do this constantly for depression and tobacco use screenings, A1c testing, mammograms; can’t we use it to remind providers to ask female patients about their pregnancy intention (shout out to our partner Upstream USA who is doing amazing work on this front), or whether they are experiencing symptoms of post-partum depression? Can’t we use it to remind providers that offering a choice in birth control methods could mean the difference between a woman finishing a degree versus managing an unplanned pregnancy?

None of this is rocket science, and yet the numbers are so saddening that we cannot assume any of these basic needs are being met. And while DRVS has built out many reports around various aspects of women’s health, in my five years at Azara I have observed how underutilized they are. Azara’s partnership with Upstream USA has been a huge boon to the development of these tools, but women’s health does not just mean reproductive health.

There is so much more we could do with a system as flexible and dynamic as DRVS. Some of that work is the slow, often tedious, process of building the right checks and reminders into care workflows, but it means that someday a discussion about menopausal symptoms becomes as ubiquitous as asking a patient if she smokes. Until we get to this place, the promise of value-based care will never be realized.

I make it sound easy and of course it is not – our healthcare infrastructure does not adequately support or prioritize this work, and care teams are overwhelmed and underpaid already. There is some good news in that maternal health is getting more attention and funding from the White House and HRSA, but if we want to improve population health in any capacity, we must embrace changes large and small in how we engage with women on their health.

I have heard such amazing stories from health centers, practices, and networks about how they use data daily to make a difference in the lives of their patients, so I know this is possible. As Angela Boyer, Chief Strategy Officer of the Indiana Primary Care Association said at Azara’s 2021 conference, referencing the work of one of her colleagues on diabetes care, “think of all the amputations that have been prevented because of your quality work…think of all the lives you have changed…making it possible for grandfathers to keep their feet so they can walk their grandkids to the park and swing them on the swings.” Whether mitigating diabetes complications or helping women access contraception, data can have a real and powerful impact on care and outcomes. Azara can help make this type of work possible and we look forward to partnering with you all as we strive for better outcomes for women in this country.

Related Articles

Surviving the One Big Beautiful Bill Act: Technology Strategies for Safety-Net Providers Facing Medicaid Cuts

Explore Insights

Automation, Access, and Alignment: What 2026 Has in Store for Population Health

Explore Insights