Extreme weather has slammed the United States over the past few months. Both east and west coasts saw sustained heat waves this summer, while other areas saw unseasonably cold weather and snow falling by the foot. In some places, extreme droughts have shriveled crops while in others, floods washed away people and property. Wildfires have devastated the central and western regions of the United States, Hurricane Ian brought destruction to the southeast, contributing to over 100 deaths, and an “atmospheric river” was inundating California as I wrote this blog.

These extreme weather events do not impact everyone equally, even residents of the same city or town. Minority and low-income communities often bear the brunt of the effects of extreme weather events and the larger impacts of climate change as a whole. Structural racism has led to poor urban planning and a lack of resources for communities of color, negatively impacting the response and recovery to and from natural disasters. The response to Hurricane Katrina is an emblematic example of the unequal impact on different communities.

Race is deeply implicated in the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina. In the city of New Orleans, damaged neighborhoods were predominantly comprised of Black residents, compared to undamaged areas. In a review of deaths caused by Katrina, the hurricane took its largest toll on the Black community. After the storm, recovery efforts were delayed and haphazard. In a survey of evacuees, 61% indicated that they felt the government did not care about them.

But why does this matter for healthcare organizations? What role can we, as healthcare professionals, play in mitigating the impact of extreme weather on the health of patients and communities?

Now, more than ever, it has been recognized and acknowledged that social drivers play a greater impact on an individual’s health than care received in a medical setting. One of these drivers is the community and built environment in which we live. The Healthy People 2030 initiative includes creating neighborhoods and built environments that promote health and safety as one of their key objectives. “Location, location, location” is a common refrain in real estate, but is equally, if not more, important in the context of community health. The zip code an individual is born and lives in is strongly correlated with their educational attainment and health outcomes.

As Sandro Galea, Dean at the Boston University School of Public Health and keynote speaker at Azara’s upcoming 2023 User Conference, writes in his book Well, “…the influence of these conditions (city, town, neighborhood or overlap of all three) suggests that our zip code is a better predictor of our health than is our genetic code”.

Location also affects the impact of extreme weather events. Flooding disproportionately impacts Black neighborhoods. Lack of greenspace and low-lying areas exacerbate the impacts of flooding; residents of these neighborhoods are more often poor and minority communities. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that severe storms may impact rich and poor alike, but the capacity to respond and recover is much lower in socially vulnerable populations.

The relationship between built environment and extreme weather also impacts chronic health conditions. Extreme heat and smoke from wildfires negatively affect individuals with asthma and hypertension. As shown in the map below, the CDC tracks heat related hospital utilization.

In periods of heat waves, there is an excessive amount of ER utilization for heat-related illnesses. In urban areas, heat islands trap hot air, making them significantly warmer than suburban areas. Low-income and minority communities are more likely to live in heat island neighborhoods that exacerbate physical and behavioral health conditions and heat waves are correlated with increased incidences of domestic and community violence.

![]() Fig 1. The CDC’s Health & Heat Tracker. The map shows the rate of emergency department (ED) visits associated with

Fig 1. The CDC’s Health & Heat Tracker. The map shows the rate of emergency department (ED) visits associated with

heat-related illness (HRI) per 100,000 ED visits by region for the period of 7/17/2022-7/23/2022.

To help address and mitigate the impact of climate change on the health of the American people, President Biden directed the Department of Health and Human Services to establish an Office of Climate Change and Health Equity–the OCCHE which was established in August 2021. The goal of the OCCHE is to, “protect the health of people throughout the US in the face of climate change, especially those experiencing a higher share of exposures and impacts.”

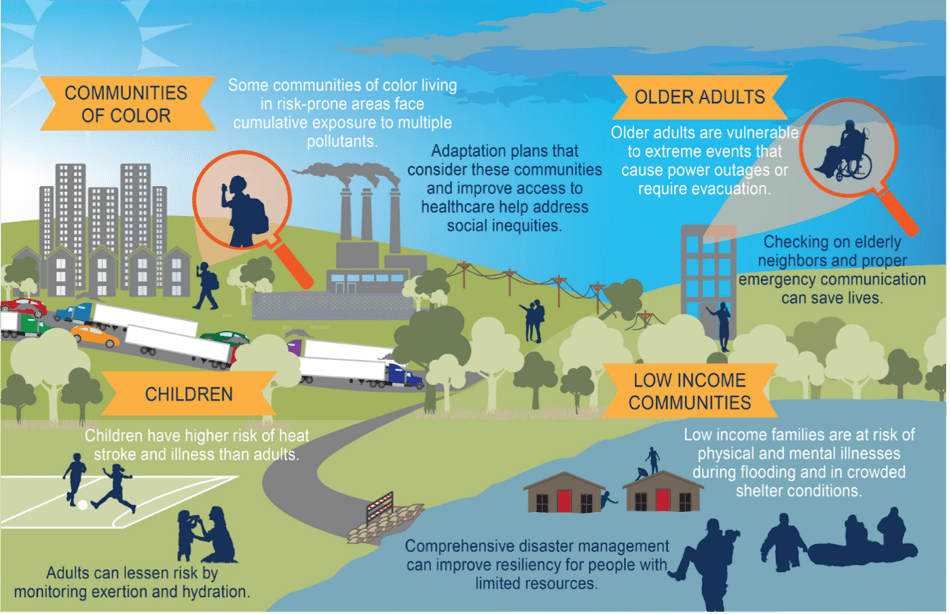

Fig 2. An infographic from the Fourth National Climate Assessment on the impact climate has on vulnerable populations.

Fig 2. An infographic from the Fourth National Climate Assessment on the impact climate has on vulnerable populations.

While looking at climate change through a health equity lens, individuals can think about an environmental justice framework. A recent Health Affairs blog posits that Federally Qualified Health Centers can, and should, promote environmental justice. Since their inception during the civil rights movements of the 1960s, FQHCs have provided care for medically underserved populations, a population that is also disproportionately impacted by climate change. Health centers have a deep understanding of their communities and their social drivers of health and by using this information, CHCs can identify areas of environmental injustice in their own communities.

This blog just briefly touches on the impact extreme weather has on health equity, but climate change is impacting health outcomes in other ways. Vector-borne and tropical illnesses are on the rise in the United States.

Lyme disease and mosquito infections like west Nile and Triple E (Eastern equine encephalitis) are becoming endemic in an increasing number of states. Wildfires threaten safety, homes, and air quality of many communities, exacerbating conditions like asthma. Droughts jeopardize agriculture and food supply chains, impacting the healthy food to which communities have access.

In the second part of this series, I’ll dive into the data and the Azara tools you can use to understand the impact of climate on your community and how to use data in response to natural disasters.

Related Articles

Socioeconomic Status, Access, and Control: Rethinking Diabetes Outcomes

Explore Insights

Navigating the Social Care Landscape: Five Lightbulb Moments from the SIREN National Research Meeting

Explore Insights